Bridging Literature and History: James Buchanan Meets an American Author

Bridging Literature and History: James Buchanan Meets an American Author

by Nathaniel Drenner, Collections Intern, Summer 2025

Politicians and Authors

When we think of major figures in history, we probably first envision people like politicians, activists, business tycoons, or military leaders. Novelists may not make the cut. Writers, though, have a life outside of their books. They sometimes even cross paths with people in power.

I am a doctoral student in the American Studies program at Penn State Harrisburg. This summer, I worked as an intern at LancasterHistory under the supervision of Dr. James McMahon, curator and director of collections. The internship centered on collections management, which relates to my broad interest in public history. However, I also had a chance to investigate one of my specific research areas: 19th century American writers.

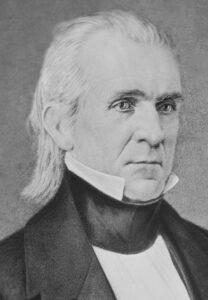

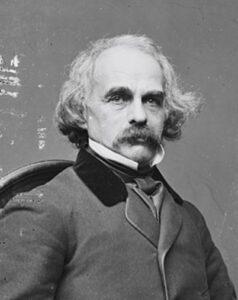

They are names you may have been required to read in school: Louisa May Alcott. Ralph Waldo Emerson. Nathaniel Hawthorne. Henry David Thoreau. These writers did not exist in a bubble. Many were politically and socially active during their time. During my internship, I became curious about any relationship that might have existed between notable American writers and the 15th president. In the build-up to the Civil War, surely these cultural figures must have at least commented on the actions — or inactions — of the Buchanan administration.

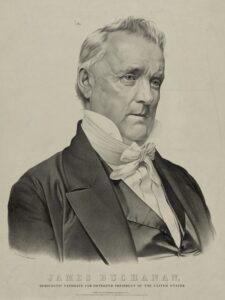

What I found was not quite what I expected. The subject has been publicly broached before, albeit briefly, in a 2004 Lancaster New Era column by Jack Brubaker. Citing a newsletter from the James Buchanan Foundation (now part of LancasterHistory), Brubaker tells us that Buchanan did have a particular connection to two authors of his time: Washington Irving and Nathaniel Hawthorne. It was a relationship perhaps more economic than cultural.

Put simply, before becoming president, Buchanan “was their boss.”[1]

The erudite Irving served as minister to Spain in the 1840s when Buchanan was Secretary of State under James Polk. Beyond that fact, I could not locate much additional information about interactions between the two men, aside from excerpts of a few official reports Irving sent to Buchanan. The more detailed — and interesting — insights into the future president come from Nathaniel Hawthorne.

United by President Pierce

Hawthorne was well connected, politically. He became friends with eventual U.S. President Franklin Pierce when they were both students at Bowdoin College in the early 1820s. During the Polk administration, Pierce helped Hawthorne obtain a job at the U.S. Custom House in Salem, Massachusetts. Then during his own presidency, Pierce appointed the writer as U.S. Consul in Liverpool, England, in 1853. A consul provides diplomatic assistance in a foreign country.

Buchanan was the senior diplomat in England at the time, serving as Minister to the United Kingdom, also an appointment by Pierce. Though he resided in London, the two met several times. Hawthorne reflected on these meetings in his notebooks, which were later compiled and published after his death.[2] These recollections, though relatively few, foreshadow Buchanan’s presidency and even suggest careful political maneuvering on his part.

Hawthorne’s first record of a meeting between the two is dated January 6, 1855. Buchanan and his niece Harriet Lane were in the area to attend a wedding, so they called on Hawthorne and his wife. Hawthorne recorded his impression:

I like Mr. Buchanan; he cannot exactly be called gentlemanly in his manners, there being a sort of rusticity about him;—moreover, a habit of squinting one eye, and an awkward carriage of his head; but, withal, a dignity in his large, white-headed person, and a consciousness of high position and importance, which gives him ease and freedom.

“Rustic” would become a favorite descriptor for Buchanan; Hawthorne used it again in several later entries. Perhaps the observant Hawthorne was detecting something innately Pennsylvanian about the future president from Mercersburg, who had settled in the then-agrarian outskirts of Lancaster City.

Political Conversations

Their meeting, though, was more than an exchange of pleasantries. In a conversation so filled with ambiguity and subtext it could have come from one of Hawthorne’s novels, the two landed on Buchanan’s political future — or potential lack thereof. Buchanan appears to be the one who broached the subject. As they talked, he declared his intent to “retire forever from public life” in the coming year. When Hawthorne voiced doubt, Buchanan “immediately responded to [the] hint as regards his prospects for the Presidency” and said that “his mind was fully made up, and that he would never be a candidate.”

Famous last words. Hawthorne believed Buchanan, but he knew the political reality: Buchanan was “the only Democrat, at this moment, whom it would not be absurd to talk of for office.” Moreover, he noted a distinct excitement in Buchanan’s mannerisms when talking of the presidency. Hawthorne surmises that Buchanan’s disavowal may have been a ploy. After all, the then-Minister knew that Hawthorne knew his rival for candidacy, Pierce. It would not exactly be sound politics to tell the president’s lifelong friend that you plan on challenging the president for his job. But, for Hawthorne, it was “a very vulgar idea—this of seeing craft and subtlety, where there is a plain and honest aspect.” Buchanan, the skilled diplomat, just seemed so darned trustworthy.

Buchanan was, of course, actively thinking about running for president. He was “coy” about it even in his letters to Harriet Lane when she returned home to the United States later in 1855. Wanting Lane to keep a low profile, he said to her, “If I had any views to the Presidency, which I have not, I would advise you not to remain longer in Philadelphia than you can well avoid.”[3]

Buchanan and Hawthorne talked politics again later the same year, as recorded in Hawthorne’s journal for September 13, 1855. This time, Hawthorne was visiting London. Buchanan complained to the writer that President Pierce had not taken Buchanan’s advice regarding the make-up of the cabinet. He also thought Pierce had “a fair chance of re-nomination” — which, of course, did not happen, as Buchanan himself became the Democratic candidate. Was Buchanan again being diplomatic toward Hawthorne’s friend, or was it a failed prediction?

Regardless, both men agreed that “the next Presidential term will be more important and critical… than any preceding one.”

What Did Buchanan Think?

I have not located any personal recollections the other way around: by Buchanan about Hawthorne. Ever the diplomat, Buchanan may have kept his thoughts on the moody New England writer strictly to himself. The two exchanged letters multiple times, which appear in collected works of both Buchanan[4] and Hawthorne[5]. These appear, however, to have been strictly business correspondence.

There is also no evidence that Hawthorne ever visited Buchanan at Wheatland, or anywhere else outside of England, for that matter. Nor did their interactions seem to continue after their careers drew them in different directions. Nevertheless, there appears to be mutual respect. In a letter, Hawthorne refers to himself and Buchanan as “personally friends.”[6] Likewise, scholar Bill Ellis notes that Buchanan once “termed Hawthorne a ‘valued’ friend”[7] — though a diplomat, of course, cannot afford to make enemies.

Despite the relative brevity of their relationship, their positions on issues of the time could be explored further. Specifically, their letters reference political controversies over the treatment of American sailors in Great Britain, the status of Cuba on the international stage, and the United Kingdom’s role in the Crimean War. The issue of pay and taxation for his position as consul seems to have been important to Hawthorne, as well.

But regarding their interpersonal relationship, Hawthorne’s feelings about the politician were clear. In a letter to publisher William Ticknor, Hawthorne says of Buchanan, “[He] takes his wine like a true man, loves a good cigar, and is doubtless as honest as nine diplomatists out of ten.”[8]

Sources Cited

[1] Brubaker, Jack. “Hawthorne Commended Buchanan’s Good Sense and Geniality; James Buchanan Knew Washington Irving and Nathaniel Hawthorne Before He Became President. He Was Their Boss.” Lancaster New Era, October 22, 2004.

[2] Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The English Notebooks, edited by Randall Stewart. Russell & Russell, 1962.

[3] Balcerski, Thomas J. “Harriet Rebecca Lane Johnston.” In A Companion to First Ladies, edited by Katherine A. S. Sibley. John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

[4] Moore, John Bassett, ed. The Works of James Buchanan, Comprising His Speeches, State Papers, and Private Correspondence. Vol. 9. J. B. Lippincott Co., 1908-1911. https://deila.dickinson.edu/buchanan/resources/fulltext.htm#Moore.

[5] Charvat, William et al., eds. The Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Vols. XVII-XX, edited by Thomas Woodson et al. Ohio State University Press, 1987-88.

[6] Hawthorne, Nathaniel. “To Horatio Bridge, Washington.” In The Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, edited by William Charvat et al. Vol. XVII, The Letters, 1853-1856, edited by Thomas Woodson et al. Ohio State University Press, 1987, p. 587.

[7] Ellis, Bill. “Introduction.” In The Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, edited by William Charvat et al. Vol. XIX, The Consular Letters, 1853-1855, edited by Bill Ellis. Ohio State University Press, 1988, p. 52

[8] Hawthorne, Nathaniel. “To William D. Ticknor, Boston.” In The Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, edited by William Charvat et al. Vol. XVII, The Letters, 1853-1856, edited by Thomas Woodson et al. Ohio State University Press, 1987, p. 210.

From Object Lessons