Armstrong Goes to the (World’s) Fair, Part 1

The 1939 New York World’s Fair

Written by James McMahon, Ph.D.

Posted by Emily Miller

My name is James McMahon and for the past year I have been working as a project archivist for LancasterHistory. My responsibilities include cataloguing and digitizing a vast collection of archival materials that document the significant role of the cork industry in the local economy. Recently, I came across a collection of photographs documenting the participation of Armstrong Cork Company in three different twentieth century world’s fairs—two in 1939 and one in 1964. Part I of this two part blog will look at Armstrong’s participation in the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Part II will explore Armstrong’s participation in the 1939 Golden Gate Exposition held at San Francisco’s Treasure Island and the 1964 New York World’s Fair held 25 years later in the same location as its 1939 predecessor.

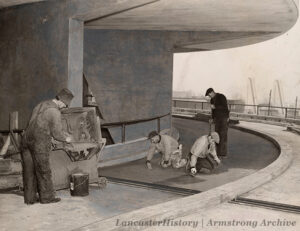

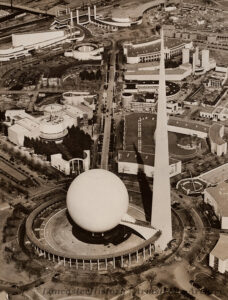

The 1939 New York World’s Fair opened on April 30, 1939; a date chosen to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the inauguration of George Washington in New York City as the first President of the United States in 1789. Despite this nod to the past, the focus of the fair was the future and how technology could pave the way for a more harmonious society. Held at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in the borough of Queens, the fair attracted over 44 million visitors over two seasons before closing on October 27 1940. Billed as heralding the “Dawn of a New Day,” the “Building the World of Tomorrow” theme was reflected through architecture, the most stunning example being the Trylon and Perisphere—striking white geometric shapes in the form of a 700 foot tall triangular pylon and an adjacent enclosed sphere that housed a utopian city-of-the-future diorama christened Democracity. After exiting the Perisphere, visitors descended to the ground level via the Helicline, a 950 feet long spiral ramp paved with Armstrong’s Monocork, a recently developed flooring material composed of rubber and cork. Monocork as well as Armstrong linoleum, resilient tiles, and other insulating and building products were also installed in various buildings throughout the fair, including the Trylon and Perisphere. In all, installations of Armstrong materials totaled more than 1,700,000 square feet.

By far, most of the Armstrong products used in New York World’s Fair buildings were resilient flooring materials, principally linoleum. Although no color images of these installations exist in the Armstrong Archive, you can almost picture what these rooms must have looked like by reading some of the descriptions of the types of flooring used and applying a little imagination. Take, for instance, the installation of cadet blue and turquoise Plain Linoleum on the exterior exhibits of the American Radiator and Standard Sanitary Corporation Building; a field of black with feature strips of dark grey in the Executive Lounge of the Continental Baking Company; or a field of midnight blue with an inset of white in the main entrance area of the World Trade Center.

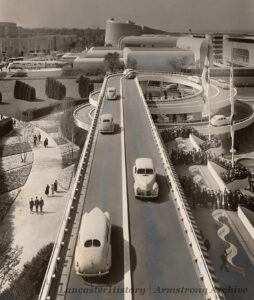

The fair was divided into seven geographic or thematic zones, arranged in a semicircular pattern around the Trylon and Perisphere. Reflecting the futuristic theme of the fair, visitors to these zones could view a variety of experimental products and new technologies. In an age increasingly dominated by the automobile (the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the nation’s first superhighway, would open on October 1, 1940), the Transportation Zone, especially the General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford pavilions, proved to be quite popular. In the General Motors pavilion, visitors experienced Futurama, a large-scale model of what a city of the future might look like; in the Chrysler pavilion, a 3-D film in an air conditioned theater, then a new technology; and in the Ford pavilion, a ride in a car on a conceptual highway incorporating modern materials and design for safer, quieter, and more efficient roadways.

“The Road of Tomorrow,” a feature of the Ford Motor Company Building, used Monocork to give visitors a safe, smooth ride on an elevated roadway that wound for more than one-half mile through and around the Ford building and grounds. Described as “a new non-slip, resilient surfacing material made of liquid rubber and cork,” the Monocork paved roadway offered visitors an “unexcelled” panoramic view of the fairgrounds. Riding as passengers in one of 36 brilliantly painted Ford, Mercury, or Lincoln-Zephyr automobiles, an average of 8,000 people per day took advantage of the free experience!

Sandwiched between the waning years of the Great Depression and the beginning of World War II, the 1939 New York World’s Fair was not so much an attempt to predict the future, but to give a positive view of what the future might hold. Although the promise of a new world based on technology was interrupted by World War II, many of the products and technologies first exhibited at the fair would eventually become commonplace, including fluorescent lights, air conditioning, broadcast television, and nylon.

In Part II of “Armstrong Goes to the World’s Fair,” we will take a look at the international celebrations held in San Francisco in 1939 and again in New York in 1964. In both instances, fairgoers not only had the opportunity to view exhibits and attractions from around the world, but a showcase of Armstrong products as well. Until then, see you at the fair!

From Archives Blog