Mr. Buchanan’s Bungled Biographies

Ulysses S. Grant has the distinction of being our first American president to write an autobiography. Grant’s two-volume autobiography, The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, was published by Grant’s close friend Mark Twain shortly after General Grant’s death in 1884. Many have speculated that Twain served as a “ghostwriter” for Grant; it is almost certain he had a strong editorial influence. The Grant autobiography proved to be an excellent profit-making venture for both gentlemen, who were equally notorious for being bad at managing money.

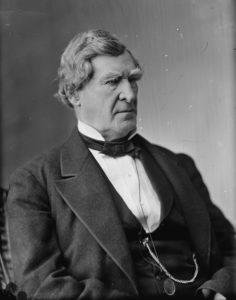

But did you know that James Buchanan is our first American president to write published memoirs? And Buchanan would have been the first with a biography if things hadn’t gone tremendously wrong for him.

Although the terms “memoir” and “autobiography” are used interchangeably by many, there is an important distinction between them (a distinction that means Grant wins, and Buchanan loses, in the race to the biography). The difference is the timeline covered in the writing – an autobiography focuses on the chronology of the writer’s entire life, while a memoir covers one specific aspect or time period.

Immediately upon leaving office in 1861, Buchanan was keenly aware of the need to defend his public policy. He had a lot of explaining to do, at least if you believed the Republicans, and he felt a strong desire to set the record straight by outlining the decades of developments that led to Civil War. Buchanan’s Attorney General and close friend, Jeremiah S. Black, offered to prepare a biography of Buchanan in order to “vindicate” his character.

Not long after Buchanan paid Black $7,000 and Black set about writing, the two came to a philosophical crossroads. Buchanan was of the opinion that “Mr. Lincoln had no alternative but to defend the country against dismemberment,” and he fully supported Lincoln’s decision to go to war after the attack of Fort Sumter. Black, on the other hand, felt that Buchanan could not and should not endorse the decision – which Black felt undermined the Buchanan administration, and Democratic beliefs that the war was unconstitutional. By November of 1861, Black and Buchanan parted ways, and Buchanan wrote to his niece Harriet, “the Biography is all over.”

Upon parting with Black, Mr. Buchanan took the task upon himself. By late 1862, Buchanan completed a draft of his memoirs, giving it the catchy title, Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion. Although the book was complete, Buchanan made an interesting decision regarding its publication – he delayed the publication until after Lincoln’s term in office came to a close, because he did not want to “embarrass M. Lincoln’s administration.” Ultimately, the book was published in 1866, after Lincoln had died. The memoirs are written in the third person and were intended to serve as a historic document, not a riveting story. Indeed, even today, Mr. Buchanan’s Administration receives a majority of 3-star reviews on Amazon, with reviewers calling it “a dry and legalistic presidential defense” and “a laborious read.”

Buchanan understood that his limited and relatively dry memoirs were not going to garner popular attention. Therefore, after writing Mr. Buchanan’s Administration, he continued to seek a biographer who could compose an anecdotal biography for the general public. But Buchanan could not catch a break. The first author he hired, James F. Shunk (son-in-law of Jeremiah Black), spent the better part of a year living with his wife at Buchanan’s Wheatland home, only to fall off the face of the earth without ever completing the task. (Buchanan resorted to writing to Mrs. Shunk, begging her to get her husband to give his notes back so the biography could be completed.) With Shunk out of the picture, Buchanan then turned to William B. Reed, who served in the Buchanan administration as minister to Imperial China and was a notable biographer in his own right (having written a biography of his famous grandfather, General Joseph Reed). Knowing Reed was a notorious procrastinator, Buchanan even offered Mrs. Reed $5,000 upon the biography’s completion, hoping to entice her to coax her husband along in making quick work of the book. Reed did his best (despite getting the cold shoulder from Shunk during multiple attempts to retrieve his biographical notes) but never finished the biography, possibly because of a fire that burned most of his notes and writing (though many of his notes still exist, and are available to view in Philadelphia).

Thus, Buchanan died without a biography, despite his multiple efforts to get one written. In 1883, fifteen years after Buchanan’s death, his heirs finally got George Ticknor Curtis to finish the job and publish a two-volume biography, Life of James Buchanan. Unsurprisingly, Jeremiah Black (writing from his sick bed 12 days before he died) was deeply critical of Curtis’ biography, even before he actually read it. “I do not of course mean to criticize a book that I have not read,” he wrote, on page 5 of a 7-page rant about all the things wrong with Curtis’ book.

This is an entry from History from the House:

A 200-year-old house once occupied by an American president has a lot of stories to tell. From an office in Wheatland’s former kitchen space, Museum Educator Stephanie Townrow digs up quirky, fascinating, and sometimes puzzling stories that reveal the hidden histories within President James Buchanan’s Wheatland. She invites readers to explore his home, meet his “little family,” and learn about the tumultuous political climate that surrounded his presidency.

From History From The House