Electing Buchanan

LancasterHistory recently acquired an 1856 James Buchanan presidential campaign medal. While some of the images and symbols on the medal are straightforward, others are not. Especially intriguing is the appearance of 32 stars on the back of the medal—at a time when there were only 31 states in the Union. Why 32 stars? The answer, it seems, lies in the contentious debates over slavery and popular sovereignty (allowing people in a territory to decide for themselves whether their territory would enter the Union a free or slave state) that began well before the election of 1856, but reached a feverish pitch in the years just before the outbreak of civil war only a few years later.

Divisions and Disillusionment

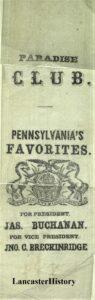

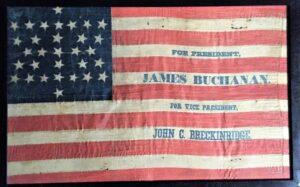

The presidential election of 1856 featured a three-way race between the Democratic Party ticket of James Buchanan and John C. Breckinridge; the Republican Party ticket of John C. Fremont and William L. Dayton; and the American “Know-Nothing” Party ticket of former Whig Party president Millard Fillmore and Andrew Jackson Donelson. Although Buchanan won the presidency with 174 electoral votes to 114 for Fremont and only 8 for Fillmore, he only received 45% of the popular vote. By the time of the election the nation was deeply divided over the issue of slavery; between those who supported its expansion and those who sought to end the practice outright. Although conflict had been building over decades, two Congressional acts passed in the early part of the decade only served to worsen the situation—the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. As a result, by 1856, the issue of slavery and the concept of popularity sovereignty (allowing people in a territory to decide for themselves whether their territory would enter the Union a free or slave state) came to dominate national politics.

The Compromise of 1850

Slavery had been a divisive issue since the founding of the nation. Disputes over slavery only worsened following the addition of new territories following the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848. In an effort to placate both sides, Congress passed the Compromise of 1850; a series of bills that included, among other things, admitting California as a free state; establishing Utah and New Mexico as territories that could decide via popular sovereignty if they would permit slavery; and passing an enhanced fugitive slave act making it easier for enslavers to reclaim freedom seekers. When California entered the Union as the 31st state, the Union then consisted of 16 free and 15 slave states.

As Secretary of State under President James K. Polk (1845-1849), the annexation of Texas and War with Mexico took place during Buchanan’s tenure. Buchanan’s role in the war was limited, however. With the inauguration of Whig candidate Zachary Taylor in 1849, Buchanan retired from public service until appointed Minister to Great Britain by Democratic President Franklin Pierce in 1853.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act

Although the Compromise of 1850 avoided outright conflict between proslavery and abolitionist factions, neither side felt the issue had been satisfactorily resolved and tensions remained high. Seeking to organize additional western territories, Congress once again took up the question of slavery by passing the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. In doing so, Congress extended the concept of popular sovereignty to the new territories of Kansas and Nebraska even though the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had prohibited slavery in those areas. Although Nebraska was far enough north that its future as a free state was assured, Kansas was next to the slave state of Missouri and appealed to both northern and southern interests.

Bleeding Kansas

Passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 produced a series of immediate uprisings as both proslavery and antislavery activists descended into the territory. The resulting violence, which lasted for several years, became known as the Border War, or Bleeding Kansas. Settlers made several attempts to draft a constitution that Kansas could use to apply for statehood. After a series of contested elections, President Pierce, a Democrat, recognized the proslavery legislature. In response, antislavery proponents established a Free State government in Topeka.

Buchanan’s appointment as Minister to Great Britain beginning in 1853 meant that he once again could not be directly connected to one of the most divisive issues of the time or to the violence in Kansas. As a moderate Democrat with a great deal of political experience on both a national and international level, Buchanan represented an ideal compromise candidate for the election of 1856. During the presidency of James Buchanan, several attempts were made to draft a constitution that Kansas could use to apply for statehood. Some versions were proslavery, others favored a free state. Only in 1861, after the Confederate states had seceded following the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln did Kansas gain admission to the Union as a free state on January 29, 1861.

The Election of 1856

Issues surrounding slavery and the violence it provoked in Bleeding Kansas shaped the concerns of voters going to the polls on November 4, 1856. Republican candidate John C. Fremont condemned the Kansas-Nebraska Act and crusaded against the expansion of slavery into any western territories. Fillmore and Know Nothings ignored the slavery issue in favor of anti-immigration policies. Buchanan warned that the Republicans were extremists whose victory would lead to civil war. A moderate Democrat who favored southern interests based on constitutional principles, Buchanan supported both the Compromise of 1850 as well as the concept of popular sovereignty as expressed in the Kansas-Nebraska Act as a reasonable approach to the slavery question.

The images and symbols used in this 1856 presidential campaign medal give evidence to Buchanan’s intent to preserve the Union while at the same time support what he considered to be the constitutional safeguards for the practice of slavery. Measuring 13/4” in diameter and 1/8” in depth, the obverse (front) of the white metal medal features a left-facing profile bust of George Washington surrounded by the words “United We Stand Divided We Fall/1856.” In the United States, the earliest use of the phrase is attributed to John Dickinson in 1768. The outermost part of the obverse features the phrase “The Union Must & Shall Be Preserved/Jackson.” This phrase (or a version very close to it) is attributed to a toast made by Democratic President Andrew Jackson in April 1830 at a dinner celebrating Democratic unity – both party and country – in response to the concept of state nullification of federal laws.

A close examination of the medal’s observe reveals a second, but less obvious connection to Pennsylvania. The name “Key” under the profile bust of George Washington refers to William H. Key (1832-1922), a Philadelphia engraver and die-sinker who began his career working with his father in the firm F.C. Key & Son in 1854. He served as Engraver for the United States Mint at Philadelphia from 1864 until 1885. Born in Brooklyn, New York, he died in Williamsport, Pennsylvania and is buried in Philadelphia.

The reverse (back) of the medal pictures a buck jumping over a canon (Buck-canon) with the date of 1856 centered between the two images. The word “AND” followed by the last name of Buchanan’s vice-presidential running mate is directly beneath the canon. Buchanan selected his running mate, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, in part to appeal to Southern voters. We now come to the question of the 32-star field. The 32 stars in the field on either side of the buck represent the 31 states then in the Union (remember, California was the last state to be admitted in 1850) and the desire of Buchanan and his party to admit Kansas and its proslavery legislature as the 32nd state in the Union. As the 32nd state, Kansas would also give the Union 16 free and 16 slave states.

Ultimately, Buchanan and the Democratic Party failed in their effort to avoid war. With rising passions on both sides of the slavery question and with little chance of promoting compromise in government or in society, secession and civil war seemed all but inevitable by the end of Buchanan’s presidency. Although a talented and skillful politician, Buchanan was no match for the forces that tore at the country in the late 1850s. With the election of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln on Nov. 6, 1860, South Carolina and six other states seceded from the Union. Civil war was about to begin.

From Object Lessons