Foiling Influenza

How Lancaster Dealt with the 1918 Pandemic

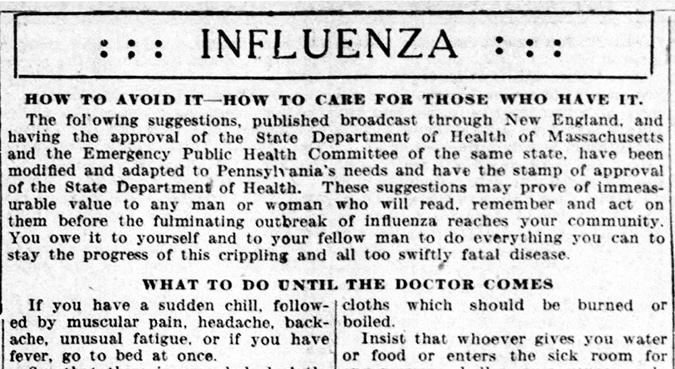

There are striking similarities and dramatic differences in how the influenza epidemic was dealt with in 1918 and how we are doing it today. We learned from mistakes made 102 years ago, but many things have parallels to today. The following are a few examples found in Lancaster newspapers from October 1918.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

In 1918 masks were worn by nurses treating sick patients, and those caring for them at home were instructed to wear them too. Masks were available from the Red Cross, but until the ladies’ groups organized to sew them by the hundreds, masks were in short supply. The materials were also hard to find, so masks had to be reused.

How to make your own mask, as instructed by the Lancaster Intelligencer on October 12, 1918.

Use four or six folds of gauze large enough to cover the nose and mouth and add tie tapes to hold it in place. When the mask is once in place, do not handle it. A wire tea strainer as a frame to hold gauze away from nose, gives more breathing space and comfort to wearers. Remember that masks to protect must be kept outside the sick room. Masks must be boiled after removal before putting on again.

Cleaning and Disinfection

Today the CDC reminds us to “wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially after you have been in a public place, or after blowing your nose, coughing, or sneezing.” Oh, and don’t touch your face.

The US Public Health Service advice in 1918 was less specific: “wash your hands before you eat and keep your fingers out of your mouth.”

It was known that “coughs and sneezes spread diseases,” and “spit spreads death,” and efforts were made to control both. Handkerchiefs that could be boiled were recommended, and they were to be kept separate until that was done. The use of “paper handkerchiefs” that would be burned was also recommended. [Curiously, although toilet paper was available since 1890, and paper towels since 1907, tissues did not come along until 1924.]

Fresh air was encouraged. One of the first things a person should do if they thought they were getting sick was to gather lots of blankets, open all the windows in the bedroom, and leave them open night and day. Trolleys had to keep all their windows open, although as the weather got colder, that was changed to only the first three windows in the car. People were encouraged to walk to work.

Central Market was still open during the height of the epidemic, and the New Era reported on October 17 that it “has been made as clean as water can make it and it has been carefully fumigated by city employees.” Pity those city employees—fumigation consisted of applying poisons.

Formaldehyde was the first choice for disinfection, but it was in short supply. The second choice was a mercury solution (0.1% mercury bichloride) sprinkled on the floor. Nurses were instructed to wash their hands either the mercury solution or Liquor Cresol, a derivative of coal tar. These chemicals would have killed both bacteria and viruses, but they are now known to be very toxic to humans and are classed as the highest (mercury bichloride) or second-highest (formaldehyde and o-Cresol) level of hazardous materials.

Contradictory Headlines

From the Lancaster Intelligencer:

October 10, 1918

“Flu” Toll About Same As Reported In Previous 24 Hrs.

October 11, 1918

“Flu” Crest Seems To Have Passed: Less Cases Today

October 12, 1918

“Flu” Takes Awful Toll In Last 24 Hrs. In City And County

October 14, 1918

City Closed Up Tight As A Preventive To Check The Epidemic

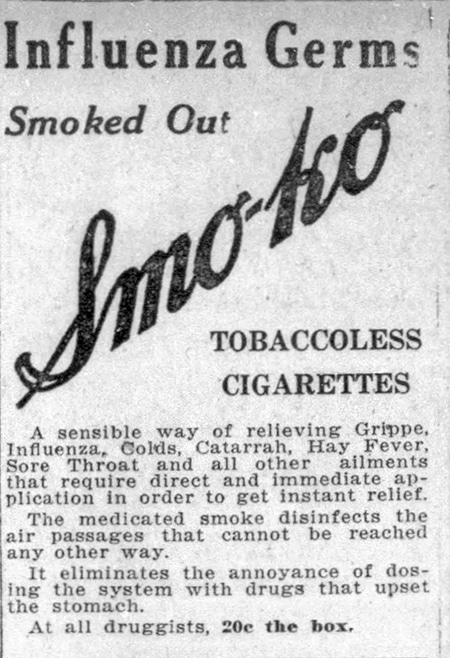

Dubious Treatments

The US had rudimentary drug laws in 1918. It was illegal to make false claims about what was in a remedy, but there was nothing to stop profiteers from making wild claims about its powers. For example:

- “Influenza Successfully Treated: Philadelphia Has Cured Thousands of Cases in Rapid-Fire Style” with Munion’s Paw Paw Pills.

- “How to Avoid Influenza: Nothing you can do will so effectively protect you against the Influenza or Grippe epidemic as keeping your organs of digestion and elimination active and your system free from poisonous accumulations … Nature’s Remedy to-night—tomorrow alright.”

The most successful marketer of its products’ anti-influenza properties was Vicks, which ran a series of ads explaining how to use VapoRub against the disease (exactly the same as it was usually used.) The ad from October 26 warned that their stock has been wiped out by demand, and people may have trouble finding it. “Act Now! Don’t Delay!” is a fine marketing tactic that may have actually been true in this case. Sales of the product nearly tripled in 1918.

Social Distancing: The First Closures

On October 4, 1918, the State Board of Health ordered the closing of gathering places: saloons, theaters, dance halls, poolrooms, and the like. Public gatherings and all indoor meetings were prohibited. Funerals were to be limited to immediate family only. Restaurants and stores remained open but were to take “reasonable precautions.”

The first controls were in effect for about a week when the city Board of Health met on Sunday, October 13. They estimated that since the epidemic reached Lancaster, there had been 6,000 cases in the city, approximately 13% of the population. The number of new cases of influenza reported on Saturday, October 12, was 500, and on Sunday 700.

Lancaster General and St. Joseph hospitals had no free beds.

The city Board decided it was time to begin stricter controls.

Essential Business Only: The Second Round of Closures

On Monday, October 14, all stores, “department stores, candy stores, soda fountains, cigar stores, shoe shine parlors and every other place of business,” were closed. Drugstores were open but could only sell drugs; food stores likewise could only sell foodstuffs. Bakeries and meat markets were not affected.

Essential Services

Barbershops were considered essential, but only for about 12 hours. Sunday evening the Board allowed them to remain open provided the barbers wore masks. That order was changed to a complete closure on Monday morning. All factories were closed, even if they were doing war work.

Laundries were permitted to stay open, provided they took in no laundry from affected homes. Milk deliveries continued, but houses where anyone was sick with influenza had to provide their own containers. Everyone else was required to boil empty bottles before returning them.

Banks and office buildings were not affected, but they were to avoid congestion. Outdoor occupations (painters, plumbers, electricians, etc.) were not closed but were ordered to take precautions.

At businesses that remained open, any employee with a cough or cold was required to stay home. This also applied if anyone in their household was sick.

Lockdown

Boy Scouts distributed placards for doctors to put on houses where one or more people were stricken that read, “Influenza Epidemic. Visitors keep out.” There had been, the board said, “promiscuous visiting, which has been the bane of the Health Board’s regulations.”

The Moose Home at 220 East King St. was set up to be used as an emergency hospital under the direction of Dr. John L. Atlee. (He caught the flu about a week later.) It was designed to care for up to 100 patients. Urgent calls went out for nurses to staff it, but response to the pleas was weak. The Lancaster Day Nursery at 144 S. Prince St. was converted to a hospital for sick children, and a temporary residence for healthy children whose parents were sick.

The stricter restrictions went into effect on Monday, October 14, 1918. They were lifted two days later.

All stores and factories were allowed to reopen. Saloons, schools, churches, and amusements remained closed, though, at the insistence of the state board of health.

City Defies State Closures

The Pennsylvania Board of Health ordered the lockdown to continue until November 5, 1918. The Lancaster City Board of Health decided to ignore the order and reopened everything on October 30. They reasoned that the number of cases was decreasing, the saloon keepers were suffering, and, besides, Philadelphia (which had been much harder hit) had reopened on October 28.

The two Health Boards tried to negotiate a solution but failed. State officials took a firm stance (or overstepped their authority, depending on one’s view of it) and took action. Thirty-two saloons that reopened received citations. Railroads were prohibited from running trains out of the city, and barriers were set up to close three main routes into Lancaster. The City began legal action against the State, and reopened the routes in and out of the city. By this time, however, it was November 5, the date slated to reopen, and the State Board took no further action.

Also at this time, World War I was coming to an end and victory headlines replaced influenza reports on the front page of the newspapers. There were a few scattered cases reported, but it clear that the numbers were finally, definitely, dropping off. The official totals reported on November 6, 1918, were 7,550 cases of influenza in the city with 301 deaths. Scholars think the actual numbers were higher.

From Archives Blog