Lancaster’s Cork Connection | Part I

Article Written by James McMahon, Ph.D.

Posted by Emily Miller

Introduction

My name is James McMahon and for the past few months I have been working as a project archivist for LancasterHistory. My responsibilities include cataloging and digitizing a vast collection of archival materials that document the significant role of the cork industry in the local economy. This blog is the first of a three-part series exploring Lancaster’s cork connection. Each of the remaining two blogs will highlight the history and importance of two local cork manufacturing concerns: Armstrong Cork Company (known today as Armstrong World Industries, Inc. and Armstrong Flooring, Inc.) and Dodge Cork Company.

What is Cork and Where Does It Come From?

When most people think of cork, the first use that usually comes to mind is that of bottle stopper. Something used by manufacturers to keep liquids, particularly wine or champagne, from spilling and casually discarded by consumers after use. But the story of cork is so much more. Believe it or not, cork is one of the most versatile, naturally occurring, renewable resources on the planet. Its natural properties make it impermeable, buoyant, elastic, and fire retardant; properties that contribute to its widespread use in a variety of commercial, industrial, and domestic applications here in the United States and around the world. Although cork is sourced from areas outside the United States, the cork industry has important historical roots in our country, especially in Lancaster.

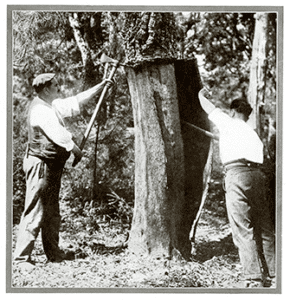

As a naturally occurring and renewable resource, cork is actually the bark of a live cork oak tree. The harvested bark is usually referred to as corkwood. The scientific name of the tree is Quercus suber; Quercus being the genus and suber the species. The cork oak tree is chiefly grown in the southwestern part of Europe and the northern coast of Africa in an area surrounding the western edge of the Mediterranean Sea. Portugal is the world’s largest producer of cork with Spain being a close second. Other cork producing countries in order of production include Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Italy, and France. A mature tree can typically grow to a height of thirty or forty feet and measure up to two feet in diameter.

When a tree reaches a diameter of approximately five inches—when it is anywhere from twenty-five to thirty years old—the first stripping of bark occurs. This “virgin cork” is rough, course, and dense in nature and is typically reserved for industrial rather than commercial use. After eight or ten years, the tree grows another coat of cork that can also be removed and used for various commercial applications, including bottle stoppers. At regular eight to ten year intervals thereafter, the tree yields its best bark and may continue to do so for one hundred years or more. At this point, a tree will begin to lose its vigor, although it is possible for a tree to reach an age of several hundred years before succumbing to injury or disease.

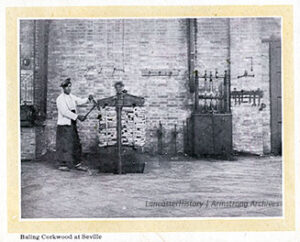

The procedure for processing the bark of the cork oak tree has not changed much over time. Once the trunk and larger branches of the tree are stripped, the bark is gathered up in piles and left for a few days to dry. The thickness of the bark is anywhere from one-half to two-and-one-half inches, depending on where on the tree it has been removed. It is then boiled and the rough outer coating removed by scraping. The boiling process also removes the tannic acid, increases the volume and elasticity of the corkwood, renders it soft and pliable, and flattens it out for convenient packing. When trimmed and sorted into appropriate grades, it is baled and sent to manufacturers for processing into finished materials.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, efforts to grow cork oak trees in commercial quantities in the United States have met with mixed results. Although early growers realized that the tree seemed to flourish best in a Mediterranean climate characterized by warm wet winters and hot dry summers similar to that experienced in parts of California, the first serious effort to establish a domestic cork forest industry did not begin until 1939 when Charles E. McManus of the Crown Cork and Seal Company of Baltimore initiated the McManus Cork Project. Fearing war in Europe would disrupt the supply of cork and lead to shortages and rationing, McManus worked in concert with various government agencies, agriculturalists, and universities to create a new supply of cork oaks here in the United States.

The McManus Cork Project had some short-term success in planting cork oak trees across California. At its height, the McManus Cork Project also mailed out millions of acorns to Americans to plant on the home front. While the effort did not succeed in creating new supplies of trees for the cork industry, the legacy of that effort can be found scattered throughout California and in places where climate and circumstance have allowed individual trees to grow and even thrive.

Although the end of World War II spelled the end for the McManus Cork Project, manufacturers like Armstrong Cork Company continued to explore options for growing domestic cork oak trees. Naturally, experts in forestry and dendrology, the scientific study of trees, were consulted. One such expert, Bishop Franklin Grant, a professor of forestry at the University of Georgia from 1929 until 1965 and an inductee into the Georgia Foresters Hall of Fame in 1969, attended at least one meeting here in Lancaster. In this photograph, dated July 1946, he is pictured in the fourth row, third from the right. Although the details surrounding the reason for his attendance are not known, Grant was obviously here to lend his expertise to some question of forestry, most likely having to do in some way with the practicality of growing domestic cork oak trees in this country.

Despite the efforts of men like Charles McManus and Professor Grant, the feasibility of establishing a domestic cork forest industry in the United States proved to be impractical. Environmental factors made the growing of trees difficult and a growing reliance on plastics and other man-made materials made the need for developing a domestic source of trees unnecessary. Yet, what of efforts to grow individual cork oak trees in Pennsylvania or even in Lancaster County?

Unfortunately, no documented examples of Quercus suber can be found in Lancaster County today; however the publication Papers of the Lancaster County Historical Society, 1950, includes an intriguing reference to a grove of cork oak trees then growing in Lancaster County belonging to Arthur B. Dodge who founded the Dodge Cork Company in 1926. According to the publication:

On a farm in Lancaster County we find several dozen cork oak trees, about two feet tall, doing quite well. The owner, Arthur B. Dodge, is very enthusiastic about their prospects since Lancaster County is on the fringe of the most favorable growing belt in the United States for this type of tree.

Although little is known about the circumstances surrounding the planting of these trees or their fate, it is not hard to imagine that these trees might owe their existence to those acorns distributed by the McManus Cork Project some eighty years ago.

The only reference to a cork oak tree still in existence today in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania can be found on the website pabigtrees.com. According to the site’s tree listing inventory, that tree is located in Wallingford, Delaware County. Last measured in 2003, that tree, had a circumference of seventy-one inches, a height of seventy-four feet, and a canopy spread of thirty-six feet. It too, may be a legacy of the McManus Cork Project, although the circumstances surrounding its planting and history are also unknown.

If anyone reading this knows of a cork oak tree in Pennsylvania (other than the example already cited in Delaware County), please let us know. However, a word of caution to the wise: Do not be fooled or misled into thinking that the amur cork tree, scientific name Phellodendron amurense is in any way related to the cork oak tree. There are at least two examples of this tree in Lancaster County, both of them located on the campus of Franklin and Marshall College. The common name of this tree refers only to the cork-like appearance of its bark and not to any properties or shared characteristics with the cork oak tree. Happy hunting!

Next up is Part II of Lancaster’s Cork Connection: From Portugal to Lancaster and Around the World with the Armstrong Cork Company.

This article was written by James McMahon, Ph.D. for the Archives Blog.

From Archives Blog