Revisiting the Meaning and Purpose of Lancaster’s Soldiers and Sailors Monument

A Sesquicentennial Celebration

July 4, 2024 marks the 150th anniversary of the 1874 dedication of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument located in the center of Lancaster’s Penn Square. Constructed of white granite and erected by the Lancaster County Monumental Association in memory of those who fought and died in the Civil War, the monument features a center pillar standing forty-three feet in height topped with an eight-foot statue of a woman in classical garb, her drawn sword facing downward signifying the end of the bitter conflict. Known as the “Genius of Liberty,” she faces north, apparently so that her back is deliberately turned toward the south; perhaps as a rebuke to those southern states seen as turning their own backs on the idea of liberty and equality for all. A single figure standing six-feet in height on each of four corners represents one of the then four branches of the armed services – Infantry, Artillery, Cavalry, and Navy.

The names of eight Civil War battles are carved on the central pillar, the battles of Antietam, Chaplin Hills, Chickamauga, Gettysburg, Malvern Hill, Petersburg, Vicksburg, and Wilderness. Several inscriptions can be found carved into the base on the north side of the monument. The main inscription reads, “Erected by the people of Lancaster County/ To the memory of their fellow citizens who fell /in defense of the Union /in the War of the Rebellion /1861–1865.” Below this inscription is the notation “Erected 1874.” Upon the suggestion of the Lancaster County Historical Society, an inscription near the bottom of the base notes the location as the site where the local courthouse stood when the Continental Congress met in Lancaster on September 27, 1777.

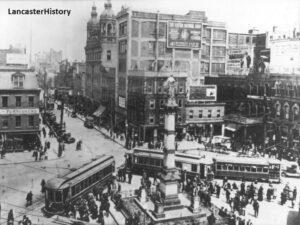

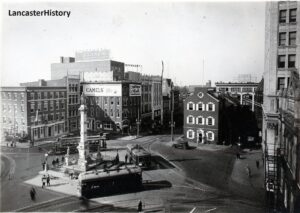

The monument has undergone a number of physical changes over the years and survived a number of efforts calling for its relocation due to concerns over increasing traffic congestion as early as the 1920s. These concerns were only exacerbated by use of the square for the loading and unloading of trolleys and buses. Although this practice ceased in 1947, calls for moving the monument to an alternate site in a city park continued. In 1972, a compromise of sorts was struck whereby a new traffic pattern created in tandem with the expansion of the Fulton Bank building created a brick pedestrian plaza that reduced the footprint of the monument and closed off traffic to the northeast side of the monument.

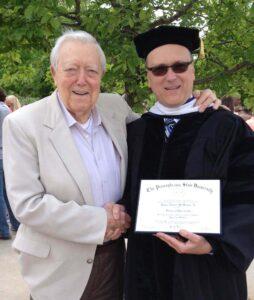

Continued calls to relocate such a prominent and heartfelt memorial in the post-war period due to safety and traffic concerns enflamed passions on both sides. On April 4, 1961, my father, a recent graduate of Franklin & Marshall College and then a police officer with the City of Lancaster Bureau of Police, presented a paper at the regular monthly meeting of the Lancaster County Historical Society (now LancasterHistory) on the history of the monument. According to the meeting minutes, “Professor Glenn Miller of Franklin and Marshall College introduced the speaker, James McMahon, who addressed the society on ‘The Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Penn Square’. Following the paper was an interesting discussion on the Civil War monument.”

The historical society published my father’s paper as an article in the autumn 1961 edition of the Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society. Titled “History of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Lancaster,” the intent of the article was “to give a true story of how this monument got here and how it has been able to resist all attempts to have it moved.” His article provided an in depth look at the history of the monument as well as some of the efforts and controversies surrounding efforts to relocate it. My father, a Marine Corps veteran, was also a staunch defender of keeping the monument in its current location. He ended his article by noting, “Besides being a monument to the fallen citizens of Lancaster, it also stands on historic ground. It is only fitting and proper that this ground should be marked off and honored as an historic spot. The spot on which the Old Court House Stood, in which the Continental Congress met in 1777, is in itself enough to justify this.” For those with an interest in knowing more about these topics, the complete article can be found here on the LancasterHistory Collections Database website.

A Concise History of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument

At the close of the Civil War, many state and local fraternal organizations were formed to honor veterans and commemorate those who died in service to the country. Chief among these organizations was the Grand Army of the Republic. In Lancaster, efforts to commemorate the sacrifices of those who had served in the War led to the founding of an association known as The Soldiers and Sailors Union of Lancaster, PA. This group would spearhead the effort to erect what we know today as the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Penn Square to honor those who died in defense of the Union. More than 12,000 men from Lancaster County served in the Union Army and that approximately 10% of those men died while in service.

In order to raise money for construction of the monument, the citizens of Lancaster embarked on a number of fundraising efforts. The Patriot Daughters of Lancaster, under the guidance of Rosina Hubley, took an early lead in raising money. A week-long fair held at what is now known as Fulton Theatre (then Fulton Hall) in December of 1867 raised $3,620.53. On February 10, 1871, the Lancaster County Monumental Association received a state charter and was authorized to receive all money raised on behalf of construction. This included $5,187.43 in military taxes held by the County Commissioners.

Armed with an official charter and money, the Monumental Association began its work. In November 1872, the Association approved a design submitted by Lewis Haldy of Lancaster. The monument was to be constructed by Batterson, Canfield, and Company of Hartford, Connecticut at a total cost of $20,000. Eventual cost would be $26,000.

Work began in the spring of 1873. As the square was excavated to lay the foundation, workers discovered a system of water pipes. As my father noted in his article, “Rather than reroute the pipes, these pipes were carefully protected to prevent the cement and stone fill from touching them. They were so boxed that a man can crawl under the Monument and examine or patch them if occasion requires. After this was done the excavated area was filled with cement and fine stone, together with huge boulders. It will be remembered that the era of reinforced concrete was not due for about half a century. The base of the Monument is therefore hollow in the center, but resting on four legs or abutments about nine feet long.”

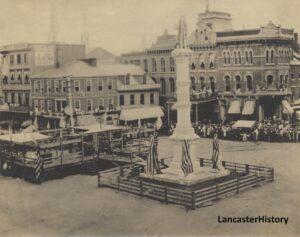

In the spring of 1874, the monument began to take shape. Appropriately enough, the monument was dedicated on July 4, 1874 with much fanfare. The monument itself was erected on a base measuring 17 ½ feet square placed within a larger 35-foot square enclosure surrounded by stockade-style fencing.

In 1877, concern over safety of the monument resulted in the Monumental Association contracting with what was then the New England Granite Works (successors to Batterson, Canfield, and Company) to erect a granite wall and iron fence at a cost of $320.00. In 1895, the date of dedication was cut into the base of the monument and in 1896, the inscription noting the significance of the location selected for the monument.

On June 8, 1931, a bronze tablet bearing the likeness of Abraham Lincoln and the text of the Gettysburg Address was placed within the enclosure by the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. It was presented to the Monumental Association by Department Commander Jacob Wentzel of Uniontown. According to my father’s article, “It faces toward the west, in the direction of Gettysburg… Although at the present time, pedestrians are forbidden to walk through the square, it is possible to get out to the monument to look at is closely or ready any of the inscriptions by asking any policeman for an escort.” Today, one need only walk on the brick pedestrian plaza by the Fulton Bank to take a closer look at this plaque (as well as several others that have since been placed on the monument).

Construction of the brick plaza extending from the Fulton Bank building on the northeast corner of the square to the monument in 1972 created the present traffic pattern and reduced the original 35-foot enclosure to the present 17 1/2 feet occupied by the monument itself. At the same time, the iron railing, added in 1877, was removed and new granite curbing was added to protect the monument from traffic collisions. On April 2, 1973 the monument was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

As a tribute to those who have given their lives in defense of the country, several bronze plaques have been added to the monument in recent years. Separate plaques honoring those who served in the America Revolution, War of 1812, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Persian Gulf War. One plaque specifically commemorates the role of African Americans in the military.

My father, who was also a Marine Corps veteran, closed his paper by noting, “Besides being a monument to the fallen citizens of Lancaster, it also stands on historic ground. It is only fitting and proper that this ground should be marked off and honored as an historic spot. The spot on which the Old Court House Stood, in which the Continental Congress met in 1777, is in itself enough to justify this.”

The upcoming sesquicentennial celebration provides us with an opportunity to reflect on the sacrifices made by those who not only fought to save the Union, but to preserve the freedoms we all enjoy as citizens of the United States of America. On a personal note, this anniversary has provided me with an opportunity to reflect upon my father’s own military and civil service as well as his work as an amateur historian. As a youth, I remember him being asked to comment on various efforts to remove or reduce the footprint of the monument and his always spirited defense of the importance of keeping the monument in its current location.

Rereading and reflecting on my father’s work has been a bit of a bittersweet journey. Although my father passed away in 2017 and won’t have an opportunity to acknowledge or participate in any sesquicentennial celebrations; I appreciate the opportunity to do so on his behalf. I am proud of his work and proud to be part of an organization that encouraged and embraced his research back in 1961 and again in 2024. Thank you for reading and for the opportunity to revisit and remember my father in such a unique and special way.

From Object Lessons