A Fatal Hotel Booking: The National Hotel Disease

In many ways, Buchanan’s presidency was a failure. While we regularly discuss those failures from a political perspective, there is one other fatal flaw to his presidency that lurks at a microscopic level.

Indeed, as Buchanan made fatal decisions during his term in office, his body suffered the fatal error of his choice in hotel accommodations.

Let’s explore.

Indecision and Ignored Warnings

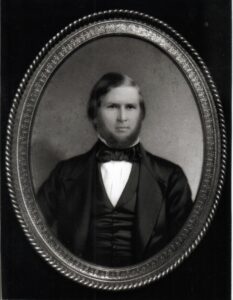

The year is 1857. Buchanan has just recently been elected 15th President of the United States the year prior. He currently resides at Wheatland in the cold month of January. In the chill of winter, he struggles to select members of his cabinet. Amidst his indecision, Senator John Slidell suggests that Buchanan go to Washington, D.C. to meet with friends before selecting his cabinet. Buchanan finds this suggestion agreeable and arranges a trip. His nephew, Elliot Eskridge Lane (called Eskridge), and Naval Officer, Dr. Jonathan Foltz, join him.

But a trip from Lancaster to D.C. was not a day trip like it is today. Buchanan thus had to arrange hotel accommodations. He made those arrangements with the prestigious National Hotel. But the hotel was currently carrying the stain of notoriety. Warnings of hotel guests contracting a mysterious disease abounded when Buchanan made his arrangements.

He decided to go to the National Hotel anyway.

Big mistake.

The Mysterious Disease

And so, Buchanan, Eskridge, and Dr. Foltz stayed in the National Hotel. All three of them contracted the mysterious disease during their stay.

When Buchanan and Eskridge returned to Wheatland, they began to suffer the effects of the disease. Doctors described it as a bloody dysentery coupled with a typhoid-like fever. Rumors spread that the origin of this illness was as assassination attempt with arsenic, but contemporary thought lays the blame on the poor sewage system at the hotel. Though the degree of Buchanan and Eskridge’s illness is unknown, newspapers soon pick up that something is not right by February 1857.

“On the 20th and 21st, Buchanan was ‘mysteriously missing,’ according to the local press, but it is certain that he was at Wheatland” (Klein, Philip S., “James Buchanan: A Biography,” Pennsylvania State University Press, 1962. P.268).

Just a few days later, Buchanan announced via the press that he was no longer accepting guests at Wheatland. Buchanan and Eskridge were, essentially, in quarantine as they fought this disease. When Dr. Foltz came to see Buchanan at Wheatland, he “ordered him to live elsewhere during the pre-inaugural period, preferably the President House where all the water came from a tested spring.” (Klein, Philip S., “James Buchanan: A Biography,” Pennsylvania State University Press, 1962. P.269).

The situation was growing increasingly worse. The President-Elect’s health was compromised with weeks to go before his inauguration.

Frequent Stops En Route to the Inauguration

Despite being sick, Buchanan persisted. He eventually chose his cabinet members. He travelled down to Washington, D.C. with Harriet Lane, Buck Henry, Eskridge Lane, and Miss Hetty. The show, as they say, must go on.

On 4 March 1857, Buchanan climbed into a carriage en route to his inauguration. But something peculiar happened. The carriage kept stopping. Why? Dr. Foltz was giving Buchanan remedies for his illness. Though the specific remedies Buchanan took remain unknown, history tells us that Buchanan took the oath of office and officially began his presidential term. The disease, for now, had been stabilized.

A Tragedy

But the National Hotel Disease would not loosen its grip. Eskridge Lane, who was 37 years old, never recovered. The effects of the disease took his life in his home at Lancaster on 27 March 1857.

As for Buchanan, the National Hotel Disease would not take his life immediately. It did, however, weaken his immune system, which eventually contributed to his death on 1 June 1868.

From History From The House