Victorian Photoshop: How Altering Waist Sizes Affects Modern Perception of Body Diversity

Before You Read: While this article is written to show that body diversity exists in the past, there are also discussions of themes relating to body image, body size, and the societal pressures surrounding sizing that may be triggering to some readers. Reader discretion is advised. Thank you!

Have you ever looked at a photograph from the Victorian era and wondered how people looked so “perfect?” Maybe you noticed that their faces were texture-free. Perhaps you observed slim figures. Soon enough, a thought might begin to form. Chances are, that thought is one of the biggest myths that circulates social and fashion history today.

That common myth is that “everyone was skinnier back then.” We might think this when we see photographs and museum exhibits that feature small waisted garments. With many examples of small figured people, we might think that body diversity wasn’t around. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Body diversity did exist. There are surviving garments throughout history that have waist sizes from 25 – 50” to prove it.

And while body diversity did exist, the myth still lives on. There are many reasons why the myth is still prominent, from museum collecting biases to visual aids such as photographs, advertisements, and portraiture. Today’s blog post examines mid-to-late Victorian era photography and how photo editing skills feeds into the myth.

How Did Victorians Edit Photos?

Photo editing techniques are not something born out of the modern era. Today, we have Photoshop, FaceTune, and Instagram filters that alter photos. The Victorians manipulated negatives by using pencil markings and scraping techniques to draw, erase, and touch up perceived beauty flaws. Period books, such The Art of Retouching Photographic Negatives (1898), have specific chapters on how to alter the bust, neck, arms, mouth, hair, eyes, and dress.

What about Alterations to the Waist?

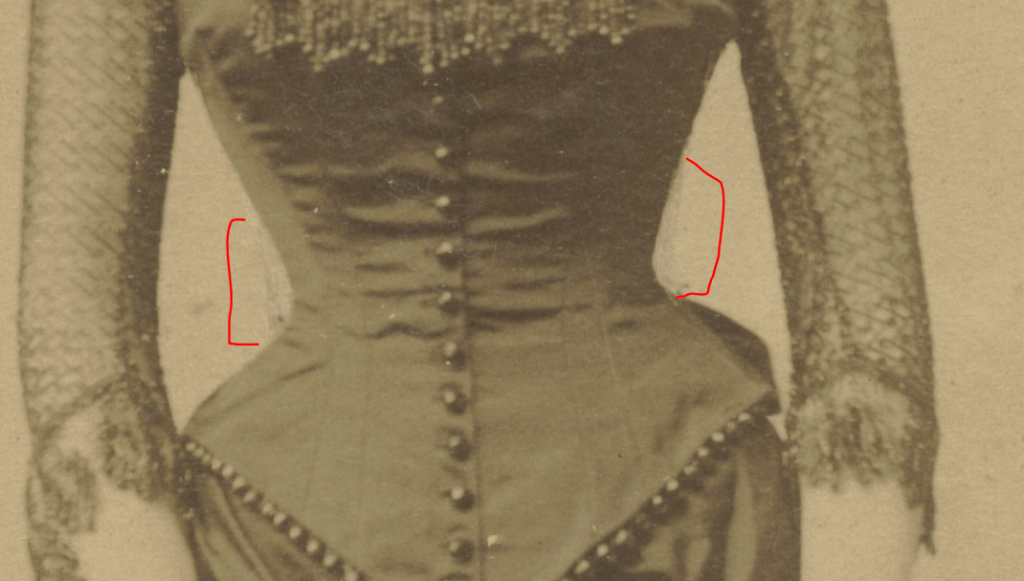

In the “Waist Question” published on 31 March 1892 in Photography, The Journal of the Amateur, The Profession, and The Trade, the columnist explains how to reshape the waist by “applying the retouching pencil either by stippling or comma-like touches.”

The columnist then goes on to describe a specific example that includes drawing the new line of the waist and then cutting off the part of the dress outside that line and placing it into the background:

“Make a curved pencil-like line commencing about half-way between the arm and the waist, gradually taking off more of the figure until the waist is reached, then more suddenly curving outwardly again over the hip, tapering off the line gradually. After this graceful curve is made, it is a case of stippling out with a pencil that part of a dress which is cut off into the background, making it match as near as possible.”

Much like photographers today, they also used lighting and backdrops to help achieve the perfect shot. As previously mentioned, editors would cut out part of the dress and apply it into the background. Photographers advise that a figured background such as a curtain or floral backdrop is best. These types of backgrounds have texture that make it easier to blend the cut-out portion of the dress into the background.

Why Are They Reducing Waist Sizes in Photos?

Much like we edit our photos today, Victorians edited photos to achieve the societal perceptions of beauty. But this idea is far more complex, and while editing photos can be a personal choice, it could also be a decision based off the male-gaze.

On one hand, individuals themselves would ask for these edits to be made to their bodies. These personal decisions demanded the skill of the photographer to be able to create such alterations, and as the 31 March 1892 publication of Photography, The Journal of the Amateur, The Profession, and The Trade points out:

“Yet no photographer who understands the whims of his customers would for a moment suggest any other style of printing bust portraits, for he knows full well that if he could not vignette off the creases of that badly-fitting dress, or remove altogether that bulky waist, he would lose many an order.”

But there is also another side to this, which reverses it back to the photographers and the male-gaze determining form and figure, as revealed in the “Waist Question.”

“‘Ambitious Amateur’ may slice off, or curve the lady’s waist after his own idea of shape and form of size.”

With each waist alteration a photographer makes based on the male-understanding of beauty, the more the line blurs between individual choice and outer forces deciding what is “pretty” or “socially acceptable” to the time. And it doesn’t just affect the Victorians who were living in this time; it also affects you and I right now.

How Editing Waist Sizes Contributed to the Modern Myth of the 18-inch Waist

When you combine unachievable beauty standards with the skills of photographers and the public’s desire to have their waist reduced in photographs, extreme cases will crop up. Sooner or later, the editing process will reduce the waist size to the extreme or to unachievable standards.

In present day when we hear the myth that “everyone was slimmer back then,” it is often followed up with, “they had 18-inch waists.” But in contemporary sources, Victorians point out that the phenomenon of such a waist measure is through editing skills.

Herbert Fry’s 1895 article titled “Retouching” discusses defects of photography and solutions to correct them. In the article, Fry categorizes defects related to the artist’s errors by eye in editing and overexaggerating lines. His prime example is the artist’s creation of a mythical 18-inch waist on a woman:

“In the last class of defect- those due to optical causes- I include such items as lack of sharpness of a principal feature at the edge of a plate, and exaggerated drawing generally. The inevitable protruding leg in a three-quarter length portrait which an artist would reduce in proportion, the exaggerated waist of a lady which measures but eighteen inches, and the cheek or nose which wants taking off, these are defects which generally prove too much for the retoucher, unless he be a draughtsman [draftsman] with some skill.”

Fry’s words give us several clues. First, they acknowledge that extreme waist reduction is a photo-editing technique being practiced. Second, they acknowledge the 18-inch waist as an exaggeration of photo editing, not a reality. Third, they classify extreme waist reduction in photo-editing to be a defect, meaning that there comes a point in the photo editing process where too much waist reduction can make the photo look off, unless it is done with someone who has skill in the process.

Finally, it reminds us that even the Victorians were aware that editing waist sizes in photographs was getting extreme. The very photographs they were editing to reflect a perceived ideal of beauty are photographs that we look at today and take at face value.

Takeaway Points

When looking at Victorian-era photographs, it is easy to accept what we see as truth. But we should not accept them as completely true reflections of the past. Just because the photo is a primary source does not mean it is an accurate one.

The reality is that these photographs are edited to show what society wanted, just like our photos are edited and filtered to show what we want today. Perceived “flaws” would be scraped out, penciled over, and retouched to project the beauty ideal of the time period.

Next time you pick up an old photograph, I invite you to look at it with a bit more scrutiny. Remember that Victorian photographs were edited to create a perceived ideal, just as we do today.

From History From The House