The Life & Accomplishments of Hong Neok Woo

May is Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month. The month celebrates and recognizes the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community and the rich history of AAPI individuals in the United States.

In 2021, Lancaster County officially recognized May as Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage month through a county proclamation. This was the first time the county did so since the month’s official designation in the United States in 1990. (OneUnitedLancaster) This year, Lancaster Asian American Pacific Islanders, a community group dedicated to supporting and bringing together Lancaster Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and their supporters, worked together with other community partners and the Lancaster County Commissioners to once again proclaim May 2023 as Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

Update on Proclamation: An official reading of the Proclamation will be given at the Wednesday, May 3rd Lancaster County Commissioner meeting at 9:15am. The agenda for the meeting is available here. The public is welcome to attend the in person meeting to support the proclamation, or watch the livestream online.

An individual mentioned in the proclamation is a Chinese American by the name of Hong Neok Woo. (Going forward, we will address him as Mr. Woo or Woo, his surname.) Much of the below information is paraphrased from William Frederic Worner’s article, “A Chinese Soldier in the Civil War,” written for The Journal of Lancaster County’s Historical Society in 1921. It is probably one of the few surviving biographies about Hong Neok Woo.

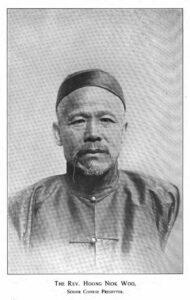

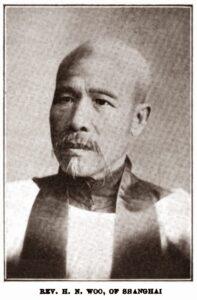

Hong Neok Woo (Wu Hongyu), 1834-1919

Hong Neok Woo (Wu Hongyu) was born on August 7, 1834 in Antowtson, a hamlet close to Changchow, China. He grew up in a farming community and his father often traveled to Shanghai to sell farm products. This led to the enrollment of his son, Hong Neok Woo, in the American Church Mission school in Shanghai at the age of thirteen. While attending the Mission school, Mr. Woo was baptized and confirmed by Bishop William J. Boone.

When Mr. Woo was 20 years old, two of Commodore Perry’s frigates docked in Shanghai on their return from their well-known expedition to Japan from 1852-1854. One of the ships, the Powhatan, would go on to carry the first Chinese delegation to the United States in 1860 (where they met with President James Buchanan!). The other ship, the Susquehanna, carried a person that would change Mr. Woo’s life forever: Dr. John S. Messersmith.

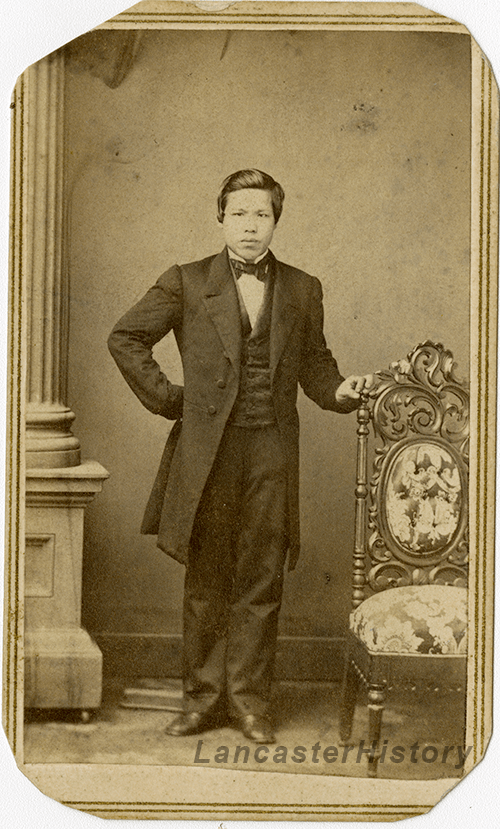

It is reported that Mr. Woo was interested in traveling to the United States and wanted to return with Commodore Perry’s fleet back to North America. Woo negotiated passage and was assigned to assist Dr. Messersmith, a surgeon aboard the USS Susquehanna. After an eight-month voyage back to the port of Philadelphia, the two continued to Dr. Messersmith’s home in Lancaster.

Woo lived with Dr. Messersmith at his residence at 40 North Lime Street in Lancaster. After Dr. Messersmith was married, however, it is unclear where Woo resided. Nevertheless, Woo would go on to live in Lancaster from 1855 through 1864.

During his time in Lancaster, Woo attended Saint James Episcopal Church. He often attended morning services and the occasional afternoon service, and spent his time with friends or out on country walks. Woo did not return to school, describing himself as a poor student, but did say he wished to become a mechanic. While his application for Lancaster Locomotive Works did not work out, he was encouraged by St. James’ organist Joseph Clarkson (a neighbor of Dr. Messersmith) to look into becoming a printer, advocating that the job had easily transferrable skills and would give him an opportunity to become fluent in English. Woo was then employed by the Lancaster Examiner and Herald as an apprentice printer for four years and a journeyman for three years before becoming a pressman at The Daily Express.

On September 22, 1860, Hong Neok Woo was naturalized as an American citizen in Lancaster County. According to William Frederic Worner, author of the article “A Chinese Soldier in the Civil War,” this means Woo became the only Chinese person naturalized in Lancaster County and was one of the first naturalized in the entire country. This is especially relevant as, 22 years later, on May 6, 1882, the United States passed a Chinese anti-naturalization law, the Chinese Exclusion Act, preventing the naturalization of Chinese persons in America and suspending immigration from China for 10 years.

Less than a year later, the American Civil War began. Woo responded to the Pennsylvania Governor’s call for the enlistment of 50,000 volunteers to protect Pennsylvania from Confederate invasion, volunteering on June 29, 1863. While Woo was satisfied, his friends were not. In his autobiography, Woo said:

“I volunteered on June 29th, 1863, in spite of the advice of my Lancaster friends against it, for I had felt that the North was right in opposing slavery. My friends thought I should not join the militia and risk my life in war, for my own people and family were in China and I had neither property nor family in America whose defense might serve as an excuse for my volunteering.”

Woo enlisted as a private in Company I, 50th Regiment Infantry, Pennsylvania Volunteer Emergency Militia. The company, commanded by Captain John H. Druckemiller, did not see combat and was sent to Safe Harbor where they camped near the Conestoga. Three days later on July 2, 1863, Woo returned to Lancaster where he was mustered into the service of the State of Pennsylvania. The company traveled to Harrisburg before moving on to Chambersburg, Hagerstown, and then finally Willamsport, Maryland. Woo was mustered out of service on August 15, 1863.

At the time of his writing, author William F. Worner estimated that Woo was the only Chinese soldier to have served in the American Civil War. Today, The American Battlefield Trust estimates that approximately 50 Chinese-American soldiers served during the Civil War, many for the Union Army. It is difficult to get a complete or conclusive account of how many Chinese-Americans served as, at the time, there was no “Asian” racial designation on the United States federal census. In 1860, there were only three racial categories on the census: white, Black, or mulatto. This, the American Battlefield Trust, writes, could mean that many Chinese-Americans listed themselves as white. They nonetheless probably endured racial prejudice and mistreatment by other white soldiers. This system of racial categorization also makes it more difficult for historians and researchers today to identify Asian individuals in the census.

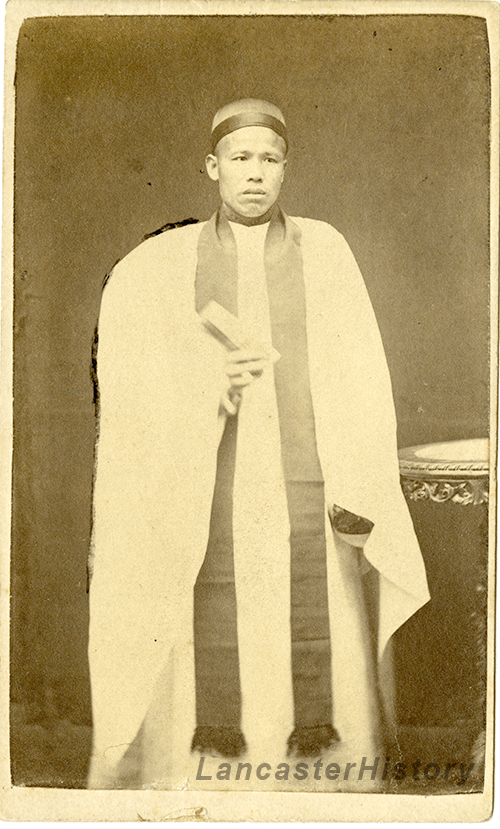

In February 1864, Woo sailed from New York City back to Shanghai. Upon his arrival in China, he was immediately offered, but declined, the position of catechist in the American Mission. Woo said he declined because of his loss of fluency (or perhaps, rusty-ness) in Chinese since he spent nine years abroad. Still, he became an assistant to the archdeacon and helped establish the first dispensary at the American Mission. This dispensary would grow to become Saint Luke’s Hospital in Shanghai. Today, the hospital is known as Shanghai Chest Hospital, which specializes in cardiovascular care.

On May 1, 1867, Woo was ordained as a deacon by Bishop Williams and was advanced to priesthood in 1880.

Woo should be most noted for his many philanthropic and humanitarian efforts which author Worner notes as being so numerous that listing them would “tax your patience and extend beyond the scope of [his] article.” The few Worner does list are Woo’s many “titles:” catechist, hospital assistant, physician, chaplain, organizer of and teacher of boys’ schools, and missionary. In particular, when he was 72, Woo vigorously fundraised for the founding of an “Industrial Home” for poor widows. Woo was successful, the home was established, and it served over 100 women. Unfortunately, at this time, we are unsure what is the contemporary name of this institution or if it is still in operation. Nevertheless, Woo’s accomplishment should be commended.

Hong Neok Woo passed away on August 18, 1919 at 85 years of age. He was buried in Westgate Cemetery, the oldest Christian cemetery in Shanghai, China. According to his FindAGrave, the cemetery is no longer extant and the state or status of his plot is unknown.

Woo’s story is a remarkable one that shows the intersection of local and global history. Hong Neok Woo is a reminder that this has always been a diverse city and a diverse county that is home to people of multiple races, ethnicities, religious traditions, and nationalities. Yet the forces that bring people here and their experiences once they arrive are not simple. Woo’s initial connection to the United States came through missionaries whose work did not always respect the traditions of the people whose countries they worked in. Woo’s transnational and hybrid identity are complex products of a colonial system that brought people together, but also imposed Western ideas and values on others. Woo enthusiastically devoted his life to Christianity, but he grounded his work in an understanding of local religions and philosophies. Worner’s article is a useful starting point for understanding Woo’s story, but more recent research by Yanfei Yin, a graduate student at the University of Houston, delved further into Woo’s autobiography and emphasizes the multiple identities he took on in China and the United States. We’ve included a link to her Master’s thesis below.

Woo left behind a legacy that Lancaster, his home city for nine years, should not forget as we welcome people from all over the world into our community. We welcome newcomers to bring their whole selves as they become Lancastrians and Americans.

Sources Consulted or Recommended for Additional Reading:

“Asians and Pacific Islanders in the Civil War,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/upload/More-Info-on-Asians-Pacific-Islanders-in-the-Civil-War-Alphabetically-by-Name.pdf

“Chinese-Americans in the Civil War,” The American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/chinese-americans-civil-war

“Rev. Hong Neok Woo,” FindAGrave.com, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/200503881/hong-neok-woo.

Stuhldreher, Tim, “County recognizes Asian-American Pacific Islander Heritage Month,” OneUnitedLancaster.com. May 6, 2021. https://oneunitedlancaster.com/coronavirus-news-roundup/county-recognizes-asian-american-pacific-islander-heritage-month/

Yin, Yanfei, “The Legendary Chinese: A Transnational Perspective of Immigrants’ Mobility in Nineteenth Century.” December 2007. https://uh-ir.tdl.org/bitstream/handle/10657/4093/YIN-THESIS-2013.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

“Woo Hong Neok,” Asian American Soldiers Memorial Hall. https://www.aasoldiersmemorialhall.org/hong-neok-woo/

Worner, William Frederick, “A Chinese Soldiers in the Civil War,” The Journal of Lancaster County’s Historical Society. Volume 25, No. 3. 1921. pg. 52-55. (A complete scan of the article is available online.)

“Wu, Hongyu (Hong Neok Woo),”Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity, https://bdcconline.net/en/stories/wu-hongyu

Resources at LancasterHistory & Beyond

Curious to learn more about AAPI history and genealogy? We’ve compiled some resources to help you research your community’s rich history!

Subject Guide: Asian-American History

Subject Guide as a Word Document [59kb, .docx]

Subject Guide as a PDF [285kb, PDF]

Fellowships

LancasterHistory also offers short-term fellowships to assist community organizations in researching their history. Learn more about our NEH-funded Fellowship program here. Those curious about the program or would like to talk to LancasterHistory about a potential project or research for the Fellowship program should reach out to Dr. Mabel Rosenheck at mabel.rosenheck@lancasterhistory.org.

From Archives Blog