The House Stretches: Updates to Wheatland

In times of company, Buchanan often joked that Wheatland stretches. As people came to visit, the rooms morphed and changed to accompany their needs. If the bedchambers on the second floor were filled, then rooms in the attic turned into guest rooms. Guests would then settle into bedchambers, shifting people about in the spaces upstairs. The parlor would change into the dining room for large functions. Furniture moved out of storage and into use. Wheatland was, in every sense of the word, an active house. And this should not come as much of a surprise, for when people inhabit a space, they update rooms, make changes, and move items from one room to another. Human occupancy creates fluidity to a space.

And while LancasterHistory remained closed to the public during the pandemic, staff sat down to research and reflect the fluidity of Wheatland in the days of James Buchanan. As LancasterHistory begins to open its doors to the public once again, guests to Wheatland might notice a few updates to the mansion. Today’s blog post reflects the research done that prompted such updates.

Historical Evidence for Harriet Lane’s Bedchamber

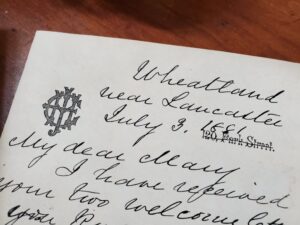

Upon the discovery of a letter written in 1861, the current bedchamber layout at Wheatland embarked on a bit of musical chairs. As Buchanan’s presidential term came to an end, both Buchanan and Harriet made plans to return to Wheatland. In a series of letters between Harriet and her friend, Sophie Plitt, furnishing discussions revealed a unique and identifying feature to the room Harriet had selected for her own. On 17 February 1861, Sophie Plitt writes:

“The covers for the mantels are to be fastened with small blocks on the mantel which are sent with the coverings. I thought the one for your room rather deep, but Vollmer said your mantel was high & required a deep fall.”

With this detail, staff set to work. They measured all the bedchamber mantles on the second floor and discovered one mantle deeper and 10 inches taller than the rest. Which room held this taller mantle? The bedchamber on West side of the mansion previously interpreted as Miss Hetty’s bedchamber.

A Game of Musical Chairs Bedchambers

With this find, a few bedchambers had to be swapped and rearranged.

Harriet Lane’s Bedchamber

Of course, the bedchamber previously interpreted as Miss Hetty’s converted to Harriet Lane’s bedchamber. This update allows for an interpretation of Harriet Lane in a new era of her life after Buchanan’s presidency. In 1861, she turned 31 years old. Far from a child, she had lived an independent life filled with frequent travel, education, and society. Though Wheatland remained her home, she traveled more often than not. This bedchamber now associated with Harriet Lane is on the far West end, an independent space for a woman who would, in just a few years, embark on a new journey of marriage, motherhood, philanthropy, and yes, more traveling.

Her new room, however, does not mean that she remained there for her entire association with Wheatland. In the years prior to 1861, she could have occupied any number of bedchambers. The historical evidence only places her in this room after Buchanan’s presidency.

A Guest Bedchamber

Harriet Lane’s previous room on the central East side of the mansion morphed into a guest bedchamber. For those familiar with Wheatland, many will recognize Harriet Lane and Buck Henry as cousins and Buchanan’s niece and nephew. Buchanan had taken both of them in as young children after the deaths of their parents. But Buchanan had 18 other nieces and nephews whom he supported. They, too, would visit Wheatland. This bedchamber now creates a space for interpretation of Buchanan’s large family and a few names that might not have been discussed in greater detail because of a lack of interpretive space.

Miss Hetty’s Bedchamber

Though Miss Hetty’s former bedchamber has a new occupant, an interpretive space for her story, as well as the story of the other domestic workers, needs telling. Rooms in which the domestic staff occupied, such as rooms in the attic and outbuildings no longer on the property, unfortunately cannot serve as a stop on the tour. To compensate, a small bedchamber in the central part of the second floor now serves as an interpretive space for Miss Hetty.

Did she stay in that room? No historic evidence thus far can confirm one way or the other. But the likelihood that she did not occupy this space achieves a greater interpretive point. It grabs hold of the idea of fluidity. Based on the 1868 house inventory, we know that Miss Hetty’s new space had bedroom furnishings. It could have served as a bedchamber for any number of visitors or current staff attending to an ailing Buchanan. From 1867 to 1868, Buchanan suffered from attacks of gout that prevented him from rising. He frequently needed assistance dressing. His weakening eyesight prohibited him from reading for long periods, and people would often read to him. During his final weeks, Buchanan’s dysentery weakened his immune system, and he caught influenza. In his final days, several family members and domestic staff were present at Wheatland, and the room’s close proximity to his bedchamber made it an ideal room to inhabit.

An Update on a Space for Domestic Workers

Buchanan employed many domestic workers over the course of his 20 year ownership of Wheatland. The majority of the domestic staff consisted of people with German, Irish, and African American lineage, with an age range as young as early teens and as old as early 60s. The domestic staff at Wheatland also had a variety of family dynamics, including unmarried workers, married workers, and married workers with children. Some lived on the property while others lived at their own place of residence.

One room integral to the interpretation of the lives and jobs of the staff is typically the last stop of a Wheatland tour. This room’s former name was the Warming Kitchen. After pulling new research from 19th century books written by Harriet Beecher, Katherine Beecher, and Lydia Child, staff found a more appropriate term for the room in American homes of the 19th century. Known as a butler’s pantry, or pantry, it connected the kitchen to the dining room. The function of the room centered on two things:

- a buffer zone between the kitchen and dining room to plate food for meal service

- storage for various pieces related to the dining room and meal service

During interpretations of Wheatland, guests heard these two points as the main functions of the room. The name, “Warming Kitchen,” however, caused some confusion amongst visitors with the implications of cooking. Moving forward with new sources, the room has a new name better suited to its function.

A Reopening

LancasterHistory plans to reopen its facilities, including Wheatland, beginning May 26. Tours will be available Wednesdays – Saturdays, on the half hour, from 10am to 3pm. (Click here to learn more and get tickets!) During your visit to Wheatland, you will hear more stories that reflect these changes to the house and its interpretation. Along the way, you’ll learn with us as we interpret the house that stretches. We’re excited to welcome you to Wheatland soon!

From History From The House